I Built an HTTP Server From Scratch. Here's What I Learned.

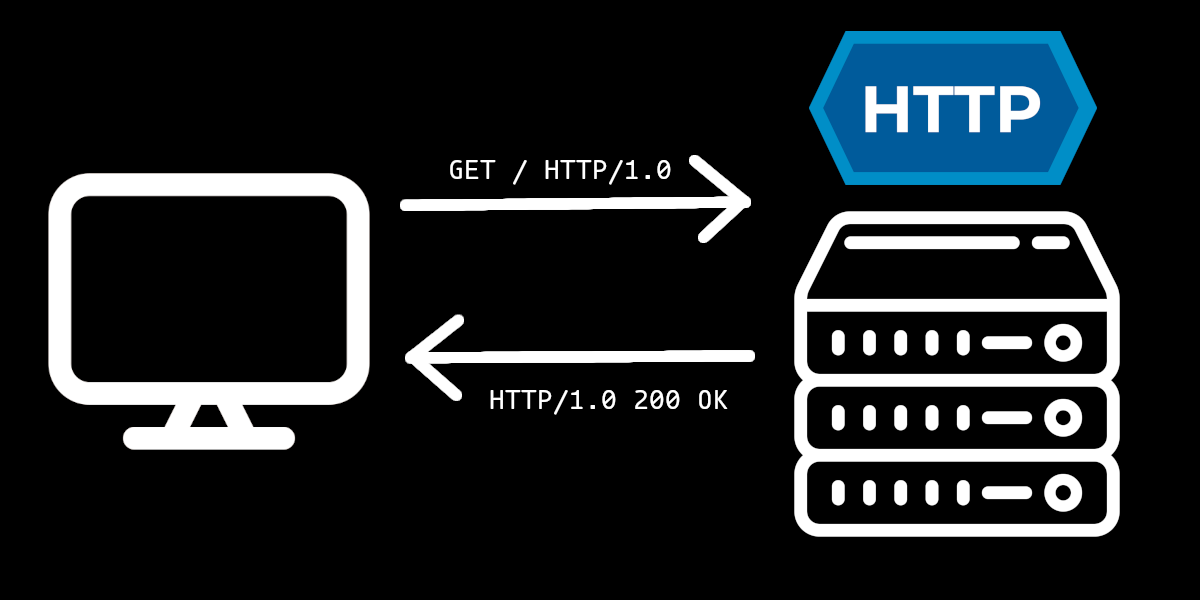

HTTP is a technology I interact with on a daily basis, whether that be fetching data from an API, designing an endpoint, or just browsing the web. It has truly become a omnipresent technology in our modern lives. And yet, I am embarassed to admit that until just recently, my understanding of HTTP was somewhat abstract. I knew how to use it, but I did not truly get how it worked. To right this wrong, I decided to implement an HTTP/1.0 server from scratch, using only the RFC 1945 specification as a guide. In this article, I will go over the major things I learned from this experience.

(In case you were curious, here is the GitHub repository containing the source code of my HTTP server).

It’s All Just Text, Isn’t It?

HTTP messages (requests / responses) are just text formatted in a particular way getting sent over the network. Before this project, I did not fully grasp this, as I always interacted with messages through an API. Of course, well-designed HTTP APIs make it so that you never need to worry about the network representation of an HTTP request, but learning about this representation was the first stage of demystification for me.

And as I said, it really is just text. The following is an example of a basic HTTP request:

GET /home HTTP/1.0

Date: Sat, 31 Jan 2026 09:06:41 GMT

User-Agent: curl/8.18.0

Content-Length: 13

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

Hello, World!This is what HTTP messages really look like under the hood. Truthfully, I had seen HTTP messages represented in this way previously, but it never occured to me that this is there actual form!

This makes the role of an HTTP server more clear. When a client sends a request, a “good” HTTP server needs take the request, validate and parse it, and construct an in-memory representation such that developers can easily access the information they need.

In this particular example, the first line is the Request-Line, which states that we have a GET request to the /home URI, using the HTTP/1.0 protocol.

Request Headers begin after the first carriage return line feed (\r\n) byte sequence, which separate lines, and end with two consecutive carriage return line feed (\r\n) byte seqeunces. Thus, lines 2-5 make up the request headers, which specify information about the requester, as well as the request body.

Finally, the request body begins after the headers.

On a side-note, the main bulk of the work for creating this server was the validation and parsing of the HTTP request. Particular, worrying about linear white space (see LWS) really added some complexity.

I Learned About TCP, Too!

Before this project, while my understanding of HTTP was decent, my mental model of TCP was honestly quite poor. Shortly after beginning this project, I realized that I would need to fix this problem, as HTTP servers are traditionally implemented with TCP.

Prior to HTTP/3.0, while HTTP was generally designed to be protocol agnostic, TCP was the network protocol the original HTTP creators had in-mind. Since then, it has stuck. HTTP/3.0, on the other hand, is designed for the QUIC protocol, a wrapper around UDP.

Before I dive into the code that establishes my TCP server, I want to give a huge shoutout to Beej’s Guide to Network Programming, which really caught me up to speed on network programming, a skill that had rapidly deteriorated since my college days. It goes into far more detail than I am about to go into, in case you were curious.

Alright, let’s look at the code from my project that sets up the TCP server:

ln, err := net.Listen("tcp", fmt.Sprintf(":%d", s.Port))

if err != nil {

s.ErrorLog.Error("problem starting server", slog.String("error", err.Error()))

return

}

fmt.Printf("Listening for connections on port %d...", s.Port)

for {

conn, err := ln.Accept()

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "could not accept connection: %s", err.Error())

}

go s.handle(conn)

}What exactly is going on here?

- The

Listenmethod creates a stream socket, binds it to an address (IP + port number), configures this address to listen for connections, and returns aListenerthat enables us to interact with this socket.- As you can see, this is doing a lot of work under the hood. In lower level languages (e.g. C), this step might consists of many lines of code.

- In my example, you may notice the IP address is omitted (nothing before the colon on line 1). This binds our socket to localhost.

- Next, we enter an infinite loop, and make a call to the

Acceptmethod on theListenerstruct. This is a blocking call that prevents further execution until a connection is established. Assuming the connection is successfully accepted, aConninterface is returned, mapped to a new stream socket for this particular connection, allowing us to communicate with the client. - Finally, we take this connection, and “do something” with it concurrently as we repeat the loop and attept to accept more connections. The concurrency mechanism will depend on your programming language, but in this case, we handle the connection using a goroutine.

Generally speaking, this is the pattern used to setup a TCP server in any language. Sure, the details may differ, but once you’ve done it in one language, it’s trivial to do in most others.

This was a real “ah-ha” moment for me. The way servers dealt with connections previously felt like magic to me, as I could not imagine how I would code it myself. But once again, taking a bit of time to learn how it really works leads to further demystification.

Content-Length is an Important Header

This particular lesson is more applicable to older versions of HTTP (including my implementation), but is still true in many cases even today. I never really understood why a Content-Length header was seemingly necessary for messages with a body until creating my own server. Allow me to share why.

Once you have established a TCP connection, and begin reading the request, you need to ask address the following question: how do I know when the request has ended?. Well, to answer this question, we first need to recognize that requests are somewhat flexible, and may not always contain certain parts.

For instance, the only required part of a HTTP/1.0 request is the Request-Line. Thus, the following is considered a valid request:

GET / HTTP/1.0

In this case, how do we know when to stop reading the request? Well, RFC 1945 has an answer to this: two consecutive carriage return line feed (\r\n) byte sequences!

I don’t believe RFC 1945 explicity states it like this, but it can be inferred from the grammar specifying an HTTP message.

The same delimeter applies to a request with a Request-Line and one or more headers. But what about requests with a body? If you recall from earlier, two carrage return line feed (\r\n) byte sequences is the delimeter used to separate Request Headers from the Request Body. Do all bodies need to end with some special byte sequence?

Well, no. Instead, HTTP clients (and servers) should specify the length of the body (in bytes) of the message using the Content-Length header! In fact, the Content-Length header is often the primary signal that a message contains a body: if this header is not present, some clients and servers will ignore the body altogether, as it becomes more difficult to read the body in its abscence. In this setup, to read the body, the server simply needs to continue reading bytes from the connection until it has read Content-Length bytes.

It’s important to understand the full implications of this. If you are not careful, a malicious user can crash your server by sending many requests with a body whose length is less than the value specified by the

Content-Lengthheader, as the server will become blocked trying to read bytes that will never show up. You can largely get around this attack vector by implementing a timeout mechanism on connections.

Most modern HTTP clients will automatically calculate the length of the body in bytes and set this value to the Content-Length header. With all this additional context, hopefully it makes more sense why that is.

Conclusion

These are the major lessons I learned working on this project. Doing this project gave me a taste of systems programming, a domain I haven’t had much experience with outside of university. There were times it was tedious, particularly parsing some of the more complex headers, but it was overall a positive experience. My only regret was that perhaps I tried to follow RFC 1945 too closely, which might have not been the best use of my time. You can likely derive the same lessons I learned with less effort (perhaps even just this article is enough)!

If you have any questions about this project, or where to get started on making your own HTTP server, please feel free to send me a message! I’d be happy to help.